14 June 2026

Beth Montague-Hellen, Head of Library & Information Services at The Francis Crick Institute & Katie Fraser, Associate Director for Learning and Research at University of Nottingham Libraries

Open access is not a new concept in the world of libraries and publishing. Ever since the advent of the internet, researchers have been trying to make their research accessible to the widest audience possible. Open access does this by removing financial barriers for readers, with costs redistributed to authors, libraries or funders. Gold open access uses the infrastructure and expertise of publishers to make articles open, often funded through article processing charges or institutional agreements. Green open access on the other hand uses centralised or institutional infrastructure and staff to provide access to earlier peer-reviewed versions of the manuscript prior to final publisher copyediting and layout.

In recent years we have come to understand that many researchers associate open access with publisher-mediated gold open access and expect this to cost thousands of pounds. But green open access is still going strong, even if we don’t talk about it that much.

Over the last 20 years there have been numerous UK policies encouraging open access. These tend to push either towards gold open access or towards green open access. Milestones include:

- The “Finch report” (2012) which centred gold publisher-supported OA in UK government policy

- REF 2021 open access policy (2018) which foregrounded green repository-mediated open access

- Plan S (2020) which proposed dual gold and green routes, but with gold publisher agreements arguably impacting practice the most

- REF 2029 open access consultation (2024) open until 17 June, which has most to say around green, including its expansion to books

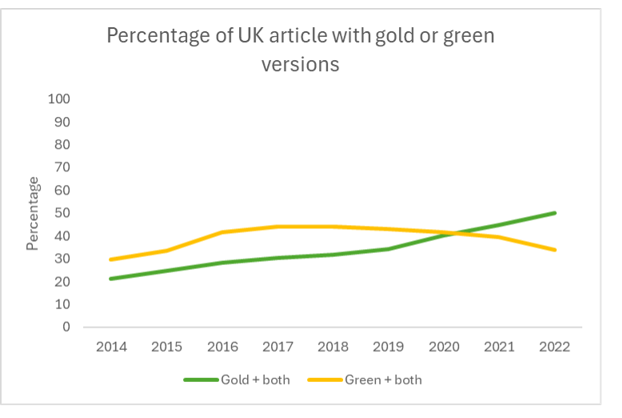

Universities have been encouraged to support and mandate green open access through the REF (Research Excellence Framework) requirements, and until 2020 we can see the UK had more content available under green open access than under gold. UKRI on the other hand seems to be pulling in a different direction with its monetary support of article processing charges and open access deals.

A graph using the Jisc transformative agreements report data (Jisc et al., 2024) to show the percentages of UK articles which have a gold version and those that have a green version.

Green and gold are often set up as alternatives, but is this accurate? Within UK Higher Educational institutions, there is substantial effort put into depositing green accepted manuscripts to institutional repositories at the point of acceptance. Some green versions get swapped for publisher versions if they’re published as gold, but many papers are both green and gold during their lifecycle. Not-quite-green pre-print versions also exist. Different versions are easily overlooked when we are assessing open access. Frequently we start by looking for gold open access, and if that’s found, we don’t look any further.

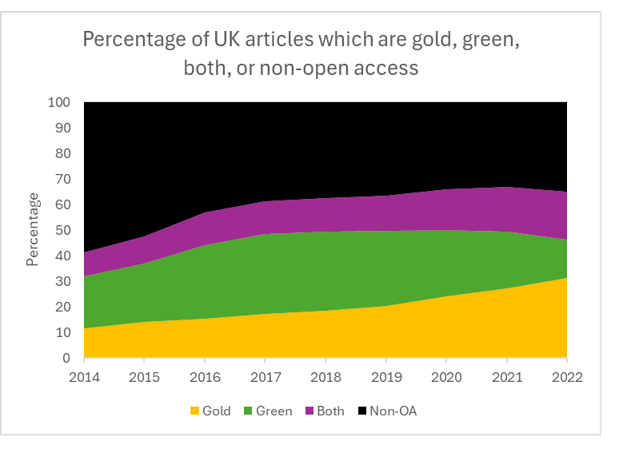

A graph using the Jisc transformative agreements report data (Jisc et al., 2024) to show the percentages of articles which are either gold (including hybrid), green, both or non-open access (including bronze).

Gold open access has certainly increased in the UK. This might follow from Plan S and the UKRI open access policy. The drive to encourage researchers to deposit their articles in a repository might also have waned since REF 2021. Rather than replacing non-open access publishing, gold open access appears to have taken a chunk of the green pie; however, the proportion of articles which have both green and gold versions has also increased.

Institutional repositories provide more than open access alone. They create an institutional record of publication. For years external bibliographic and bibliometric systems were the only way an institution could find out what publications had been produced by its own staff, other than asking them to submit and record details directly.

Now, advanced repositories and metadata harvesting offer a route for the institution to pool data about what is being published. Sources include CrossRef, ORCID and Jisc Publications Router. These capture most of the institutional record seamlessly and offer user-friendly routes to fill in any gaps. Repository infrastructure largely operates behind the scenes. Web users rarely visit the homepage of a repository, any more than they would visit the homepage of a publisher’s journal portfolio. However, individual article pages and PDFs are found through search engines, aggregators, and plug-ins.

A myth that persists is that green is a second-class route to open access, and that gold is the gold standard. Researchers often prefer to access the Version of Record. When searching for reading material, they are seeking quality peer reviewed literature, and may be using the final formatted publisher version as signal for quality. When it comes to their own papers, they may be concerned that papers published green open access receive less attention. Nonetheless, a recent study from Huang et al (2024) suggests that green open access may be attracting a more diverse audience of readers and citers.

With the advent of publicly available generative AI such as ChatGPT we could find that access to articles through a repository becomes an equal player to gold in the eyes of readers. Where algorithms and computational tools are mediating the search for knowledge, the format that this information comes in ceases to matter. A repository provided word document is as easy to access as a publisher provided pdf and it may become less and less obvious to readers where the information came from.

Both gold and green open access are embedded in the scholarly landscape, but they don’t serve the same purpose. As the drivers and mandates around open access continue to shift, we will almost certainly see further changes in the balance between these two modes. However, when someone suggests to you that open access equals gold open access, we’d like you to challenge that statement. There is room for green. Maybe there is room for both.

Links & References:

Finch Group Report (2012) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Finch_Group_report.pdf

REF 2021 Open Access Policy (2018) https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20180405121445/http://www.hefce.ac.uk/rsrch/oa/Policy/

Plan S (2020) https://www.coalition-s.org/plan_s_principles/

REF 2029 Open Access Consultation (2024) https://www.ref.ac.uk/guidance/ref-2029-open-access-policy-consultation/

Jisc, Brayman, K., Devenney, A., Dobson, H., Marques, M., & Vernon, A. (2024). A review of transitional agreements in the UK. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10787392

Huang, CK., Neylon, C., Montgomery, L. et al. Open access research outputs receive more diverse citations. Scientometrics 129, 825–845 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-023-04894-0